The enigma of Jerusalem, the mystery of the city’s spirit, sanctity as an urban riddle – these are the themes at the center of Leora Laor’s exhibition. The enigmatic nature of her works relates mainly to the temporal dimension – theatrical and fantastic, a product of computerized digital processing.

In the exhibition, the artist combines two series related to sacred sites in Jerusalem: the Meah She’arim neighborhood is photographed in the series “Wanderland” (2002-2004), and the Church of the Sepulchre is the subject of the series “Pilgr-Image” (2010-2015). Through the representation of the believer at these sites, Laor sheds light on the conflicted human condition in contemporary society. Her works emphasize the yearning for a metaphysical dimension in the life of modern urban man, awash with feelings of alienation and loneliness. Her photographs seek to convey human strength and weakness as one, using bright colors, unexpected magnifications of the frame, and more.

In Laor’s works, tension can be felt between private and public territory. She is influenced by the conventions of cinematic photography, although she locates her images in reality rather than in a fictional world. A she explains it, “the public space is the space where the photographer and the photographed object reflect each other.”

The titles of the series contain a double meaning. In “Wanderland,” the word “wander” refers to wanderers in the general, and the Wandering Jew in particular, as opposed to “land,” which symbolizes rootedness. In “Pilgr-Image,” the division of the word “pilgrimage” emphasizes the word “image,” reflecting Laor’s preoccupation with images related to this theme. According to her, “like pilgrims, I collect remnants. The pilgrims I have photographed become the remnants.” The artist focuses on the participants of the religious ritual, the act of worship itself. “In many of her images devout women in kneeling positions, reclining on the slab, are gazed at from above, and from behind, their faces often covered in isolation where they are di-contextualized or grouped together and on their own.”

Laor is interested in the interruption of daily life, in the presence of figures that seem to emerge from their context and undergo a transformation, appearing against a blurry, semi-abstract background (sometimes recalling the works of German painter Gerhard Richter). Her works repeatedly express a yearning for a different time, for worlds that open up momentarily before they elude us forever. These realistic-fictional materials reveal to us the artist’s world of photographic poetry. Her figures – like those in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” – are tenuous. Despite being definite figures photographed in specific conditions and places, they seem to have emerged out of nowhere.

Pilgr-Image #10001, 2009-13, Pigmented Inkjet Print

Abstract:

Rather than focusing on modern Jerusalem, Leora Laor’s photographic gaze is centered on Mea She’arim -- the ultra-orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem that echoes the Jewish ghettos in Europe prior to World War II. While punning on Mea She’arim as wanderland/wonderland, her gendered spotlight is mainly on the female contrasting with the Jerusalem stone in mesmerizing spiritual and troubling light. The paper will analyze the complexity of these images, especially the object of desire of the enchanting fleeting girl in traditional, baroque-like theatrical dress and white socks, projecting a state of anxiety. It is Laor’s variation of the Wandering Jew in art, or rather the neglected depiction of the wandering Jewess, a symbol with whom the artist identifies. Laor, a secular contemporary artist and a winner of the Constantiner prize for photography, whose mother is a Holocaust survivor, reconnects nostalgically to the past her mother has left behind, hoping to redeem it through art.

Untitled #100, 2001-3, Digital C-print

The setting of Wanderland is the ultraorthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim. What is your personal feeling about this place and how would you want people to experience it while looking at your pictures?

I was born in Jerusalem. Mea Shearim was always an ‘isolated island’ within the city, a neighborhood filled with mysteries and secrets for the outsider. At first my knowledge about this part of the city and its inhabitants was very limited. Growing older and out of curiosity, I began exploring Mea Shearim through my photography. The neighborhood is known as an ultraorthodox intimate society. The Haredim chose to live separated from the outside world, imitating the lifestyle of their ancestors from Eastern Europe. That’s why tradition is upheld and modernity is scorned out. As a visitor in Mea Shearim, one immediately feels like an outsider. My work is ‘straightforward street urban landscape photography’. I am a storyteller in the sense that I observe ordinary people on the street and that I try to catch their inner world. I always look for tension between the private and the public domains. I am interested in the ‘other’, the stranger, the unknown amongst the known, and the unfamiliar amongst the familiar. I realized that my work talks about me as well as about the ‘other’. It happened that while I was editing an image I discovered a new layer of meaning, one different from reality. The eye emphasizes, ignores, escapes, edits and balances to make the photograph adjust itself finally to whom we are. On a personal level, both of my parents made the ‘Aliya’ to Israel when they were children, in 1926 and 1944. They emigrated from Eastern Europe where Yiddish was the second language. My mother was the only survivor of her family from the Holocaust. She was fourteen years old when she came with the ‘Youth Aliya’ to Israel. Mea Shearim became thus for 82 De term “Aliya” wordt gebruikt om de joodse emigratie naar Israël doorheen de eeuwen aan te duiden. 51 me a reminder of her early lost childhood. Particularly Wanderland #100 is an homage to her. (Afb. 1)

What does it mean to have your picture taken in this culture and do people behave differently when they see you with your camera? We also wondered how you dressed while working in Mea Shearim?

Religion and modesty are the two main issues for the ultraorthodox Jews in Mea Shearim. The Haredi community closes itself to any media whatsoever: television, cinema, secular 52 newspapers and photography as well. The Ten Commandments mention: “You shall not make for yourself a carved image or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above.” That’s why in the orthodox community you are not allowed to be photographed or hang a picture or portraiture at home. Entering Mea Shearim I dressed myself 'properly’. I covered my hair and put on a very conservative long dress with long sleeves. I was playing with a very thin border between their rejections and my desire to photograph there. Surprisingly enough, entering Mea Shearim as an artist – as opposed to a photojournalist – equipped with a camera, gave me the inner power and the ‘shelter’ to do so. The first reaction of most people that saw me and my camera was covering their faces or turning their back to me. Some children even ran away. Recently I walked by this neighborhood and I felt like a stranger. For me the place had lost the ‘aura’ I had felt years ago. Streets have become dirtier, more neglected and very crowded. Now I saw just two colors dominating in the streets, namely black-and-white, and I questioned myself if this is still the same place where the Wanderland series was taken?

What is the story behind Wanderland? Can you explain the title? Does it refer to the tale Alice in Wonderland? And why did you change ‘wonder’ into ‘wander’? Do you maybe refer to the diaspora and the Promised Land?

The name of this series unfolds a double meaning. ‘Wander’ concerns the human wandering and the Jewish wandering. On the other hand, ‘Land’ signifies permanence and deep- 53 rootedness. Mea Shearim, as already mentioned, evokes reminiscence or loss associated with the old Jewish lifestyle in the Eastern European shtetl. As second generation of a Holocaust survivor, I found myself looking for images that had some references to the stories I heard in my family’s home. The association with Alice in Wonderland was my intention and is almost impossible to avoid due to the similar connotation. The fantasy book was written by Lewis Carroll in 1865. Up until this period of time, this type of genre was used as satire, a religious or a moral preach. In one of Carroll’s letters he had declared: “I can swear that there is no religious preaching. Actually there is no preaching at all.” Alice in Wonderland blurs the borders between reality and dream, resulting in a world of unclear ‘reality-fantasy’. The rules of nature have become distorted as objects and creatures change their size and time stands still. Furthermore, Alice's identity is one of the main philosophical issues in the book. I arrived at Mea Shearim in a ‘neutral’ manner, without intending to get into political and social commentary. My intent was on creating a fantasy world of these people who imitate the old way of life as it was lived by their ancestors in nineteenth century traditional Eastern Europe. It is clearly noticeable that there is a distortion in life roles there. For example: already early little girls become ‘mothers’ as they help out their own in raising their little brothers and sisters. Moreover, the young girls are dressed like their mothers, which in turn, distorts the role models even further. Childhood, as an extended period of life, is very short lived due to their reproduction beliefs. Eventually, these little girls become the heroines of my Wanderland series.

Untitled #101, 2001-3, Digital C-print

…In the last part of this essay, the photographs of the Israeli artist Leora Laor examine how contemporary art of the postmodern period relates to the concept of happiness. Laor, winner of the Constantiner prize for photography (2005), Chose to base a photograph on the scene from an Israeli absurd play called Osher, happiness in Hebrow, written by Michael Gurevitch. Osher is also the name of the anti-hero of the play where comic situations emerge out of puns on Osher/Happiness playing the name against the noun. When the word Osher is uttered we are not sure whether the actors are referring to the concept or a person by that name. In the prologue the spectator is instructed to do the following:

"And there's just one thing I want from you: lean back and be happy. What our play play What our play called? Osher! Happiness! Like the TV. Be happy. We love you. Because you're our audience and we're your theatre. The Khan Theatre-now More than Ever. Why? Because. (Bursts into laughter). But first of all, to get us into the atmosphere, I'd like to introduce our stars who will perform the Dance of Happiness!"

As in a television commercial, the spectator is given instructions as how to feel and behave, that is, "be happy" ironically suggesting that happiness can be commodified and tailored to instructions. However, Osher Happiness is murdered both physically and metaphorically, and the dance turns out to be a dance macabre. Apparently, the play deconstructs the concet of happiness.

Like the play itself Laor's photograph is anything but happy...

Cover Image: Leora Laor, Happiness #2 (Homage to 'Osher'), 2005

The individual within an urban setting is the subject of Leora Laor's photography. Like the work of Beat Streuli, who has chosen his subjects randomly from the stream of passerby on the streets of Tel Aviv, the images made by Laor capture the ambience of the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Mea She'arim in Jerusalem . The images are blurred and manipulated with digital technology, disarming the viewer with their elusiveness. Yet these photographs are clearly situated in reality, and Laor's depictions reveal the intimacy and diversity that characterize moments in the life of this insular community. The aim is to show familiar scenes, but in an oblique fashion, creating grainy yet luminous pictures of figures who appear evanescent within their traditional setting. With a remarkable sense of restraint the artist has mediated between the inner, spiritual world found in this Orthodox neighborhood and the surrounding secular environment.

|

|

Installtion View of Dateline Israel: Recent Photography and Video, The Jewish Museum, New-York, 2007 © The Jewish Museum, New-York

Two conflict lie at the heart of 'Dateline Israel', a compelling, but uneven exhibition of new photography and video art at the Jewish Museum. The first, which you might call Israel's internal, existential crisis, concerns the tension between the past and the present. The second, Israel 's external, political crisis, relates to the conflict with the Palestinian Arabs. These are both major issues in the Jewish state, so it is hardly remarkable to see artists take them on. What is surprising . However, is that so much of the show's strongest, most memorable work seems limited to the first category.

...By contrast, the best works in this exhibition do not try to impress upon viewers a particular view of Israel or human nature. They do not assert meaning they create it.

Like Mr. Frydlender's piece, Leora Laor's nine-photograph installation focuses on 'haredi' culture, but her images play off one another to suggest an ultimate concern with that community's elusiveness. Her subjects are typically seen from behind; they hurry away, avoiding the camera. Something much more than simple documentation is at stake: the morality and limitations of photographic representation...

Untitled #107, 2001-3, Digital C-print

..Well, that is what the insiders have to say. What more can I add? I spend a lot of time talking to artists and realize that for them the least concern is trend. The idea of trends feels too much like commercial hype. Appriciation and understanding of their vision by others with the hope of sustaining their creative process is what concerns them most. Everything else is fluid. Is not the need for nerattive depth, color and even new larger scale a type of pictorialism? I feel in love (heat) with the photograph recently, the photograph was by Leora Laor, Untitled #154 that was shown this fall at Andrea Meislin Gallery. It was 32x42". Except for the fact that it was a photograph it was almost timeless, painterly. I felt as if I were eavesdropping on a beautiful, yet awkward moment, the rush of a voyeur. The predominate mood was quit longing and detachment filtered through an amber and absinthe-green palette. There were historical and layered suggestive hints, that allusions and my memory reinforced every time I visited. My soul welled with desire, but in the end, it will be a lost love. I wait to see it published somewhere, so I can rip the page out as a souvenir. So what do I feel about trends? Most of them mean nothing to me. Technology is not a trend; the demand for an artist to create is not one either. The struggle between art and life and fashion and what defines them is constant..

Untitled #154, 2005, Digital C-print

In this impressive show of photographs, "wanderland #2", Israeli artist Leora Laor pushed her medium far into the the realm of subjectivity and emotion. Surfusing grainy scenes with a saturated palette reminiscent of cintage postcards, Laor isolates heighlightened moments of human longing or frailty.

Part of the drama here derived from the subjects' or in rehearsal. In Happiness ("Osher", Homage to Michael Gurevtich), 2005, a man and a woman face each other with clasped hands, yet the pregnant moment is one of ambighity, because the expressions on the subjects' faces are blurred. the postures imply a prelude to a tryst, a parting, or an act of violence. Another image, of two women ballroom dancing, was shot clandestinely during a dance class and portrays an unself-conscious instant of flirtation that might not heppen outside the confines of the room.

The lonliness conveyed by Laor's portraits of individals nods to Edward Hopper as well as Philip Lorca-diCorcia, who also manipulates lighting and color to highlight the psychologhical space his subjects. In Laor's photo of dancers socializing after a class, one man sits alone at a table littered with half-empty plastic cups, a conteporarycounter-point to Picasso's Absinth Drinker. Half of his face and his eyes are obscured in shadow, while his posture connotes dejection.In another portrait, a forlorn-looking woman caught in profile is brought into strak relief against an intense chartreuse axpanse reflecting the ghosts of black picture frames (Laor took it at a photography fair). Of course, the reflection of the viewer and the black frames in the gallery were also trapped in that same amber, momentarily conflating two worlds of looking and solitude.

Happiness #2 (Homage to 'Osher'), 2005, Digital C-print

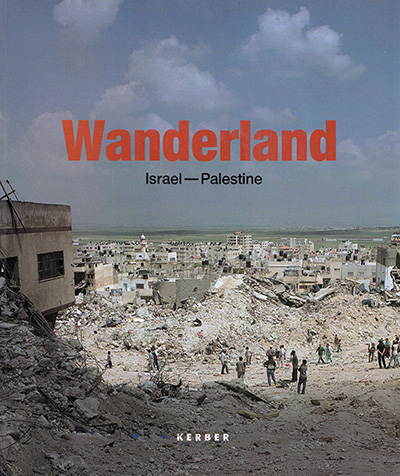

…The main title "adopted" from the photographic series of the some name by the Israeli artist Leora Laor, points in a deliberate contradiction to human wandering and a permanent land, and to that extent signal the mutual claims to a permanent homeland or to migration of the opposite party in each case that ultimately defines the Israel-Palestina conflict. So Israel's and its Palestinian neighbours' persistently unstable political, social and cultural situation is the theme. (p.29).

…The question about individual and community also accompanies Leora Laor's Wanderland (2002-2006) series, but in a different form. This confronts us with street life in Jerusalem's orthodox Mea Shearim District. We feel that we have been shifted into a different era. It is difficult for outsiders to imagine that this closed and cheerful world, presented above all by young girls and women, is in the middle of the city that is at the center of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Laor's powerful, magical images describe facet of Judaism that even rejects the state of Israel, thus working against clichéd ideas of that country. (p.33)

For her second New York show, this Israeli photographer refines a technique she used in her first, surreptitiously recording people in public and allowing her distance from the action to create a soft, grainy haze over the resulting image. Because several of her subjects are actors onstage or dancers in rehearsal, Laor's artifice is far more apparent this time around. But reducing her cast of characters, often to a solitary figure, helps focus and intensify the drama, and keeps it from dissipating at this larger scale. In a world resigned to isolation, Laor seizes upon the few moments when two people touch, but she doesn't pretend that they're a sign of hope.

To Americans, it seems Israelis know only violence, or the threat thereof. Our newspapers and magazines bombard us with images and articles about failed peace talks, checkpoints, bombings, Katyusha rockets, hatred, misunderstanding, recalcitrance.

But two evocative exhibits in Manhattan by Israeli photographers make the case that there is life beyond the theater of war. At the 92nd Street Y, Dinu Mendrea's black-and-white photographs do not ignore the violence, but instead take the second intifada as its expressed backdrop, showing Jews, Christians and Muslims either before or soon after violence has erupted.

Leora Laor's photographs, displayed at the Andrea Meislin Gallery, stay mum about the killing in Israel, instead featuring anonymous men and women dancing, acting, drinking or thinking. Yet Laor's art, like Mendrea's, is not escapist. Alienation, sentimentalism and a brooding sense of loss characterize her photographs, making one wonder if anyone but an Israeli could know such pain.

Mendrea, a 36-year-old Ukrainian immigrant, titles his show “Trying to be 20 in Jerusalem.” Yet the age range seems either irrelevant or beside the point throughout most of the 26-photo show. One of the most perplexing images, titled “Purim,” depicts four chasidic men chatting, their backs to the camera, while a fifth man is sprawled on the floor behind them, face up, in a drunken stupor. They are in the fervently Orthodox community Mea Shearim, celebrating a holiday during which getting drunk is an accepted custom.

...Alienation is as present a theme in Mendrea's photographs as it is in Laor's. But Laor's show, entitled “Wanderland #2,” is also a stylistic counterpart to Mendrea's. Her photos are shot mostly in color and on a digital camera. They are highly doctored and much larger than Mendrea's, giving a painterly quality to a dozen or so works on display that are stunning.

Take the opening photograph placed on the wall adjacent to the entrance. It is a four-foot-high, six-foot-long image of a balding, portly man gripping the hand of a morose, young woman who is looking away. The couple stands off-center, to the right of the frame, against a beige stucco wall and deep purple curtain bathed in a sultry afternoon light. Like most of Laor's photographs, the image is severely out of focus, establishing a conceptual distance between the subjects and the viewer. The man and woman seem to be speaking past one another — alienated from a love that, perhaps, once was.

Like this picture, taken from a play called “Happiness,” many of Laor's photographs are of theater or film performances. In another picture from the same play, we see the profile of a solitary man, out of focus again, his face looking out into the dark distance, away from the viewer. A hazy curtain, blue at the top, white at the bottom, contrasts with his black blazer and chocolate brown pants. His exact thoughts we cannot know. But we can only imagine that they are somber, lonely and deep.

Though Laor has made a name for herself with her beautiful, despondent images — her work is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as in other major museums around the world — these are perhaps her most heavy-hearted. After more than two decades of marriage to the renowned Israeli painter Michael Sgan-Cohen, during which she only sparingly took photographs, Laor is now widowed. Since his death in 1999, Laor has begun photographing again, and the resultant images speak from the heart of a bereaved wife, and a smarting Israeli.

Perhaps no image captures her despair more than the one that hangs behind the curator's counter at the Meislin Gallery. It depicts the backs of a man and woman, each with one arm draped over the back of the other, as they look over the greyest of blue seas. The woman's orange-red hair is tied in a bun; the man's black hair is covered by a fedora. The flatness of the subjects likens Laor's work to the Realist painter Gustave Courbet, their emptiness to that of Edward Hopper. The image is taken from an old video. And how fitting, moreover, to learn that that film, and Laor's photograph of it, is titled “Victims of Duty.”

Adultery, 2004, Digital C-print

Chelsea 's splendid Andrea Meislin Gallery, which specializes in modern photography, presents a second exhibition by Leora Laor, one of the Israel 's most fascinating photographers. Titled "Wanderland #2", the work focuses mainly on the all-embracing topic of the human condition in modern society. Using extreme colors, enlargement and other techniques, Laor creates works that are at once corporeal and frail, haunting and warm, and exquisitely beautiful. The exhibition features three main groups of work – lone portraits, couples, and still lifes – the former of which brings to mind 19 th and 20 th century portraiture, especially the works of Marry Cassatt and Edward Hopper. And, like Hopper, what governs here is alienation, detachment, loneliness, themes which Labor accentuates further by turning to theater and dance classes to showcase human fragility. Laor was the recipient of the Leon Constantiner Photography Award for an Israeli Artist in 2005. Her work is in private and museum collections worldwide, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York , the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and the Gemeentemuseum den hag, The Netherland – Andrea Meislin Gallery.

Untitled #151, 2005, Digital C-print

Yahav-Brown was born and raised in Israel, but his work isn't identifiably "Israeli." Israeli photographer Leora Laor lives in Jerusalem, and her subjects are Israeli, so that makes her work literally "Israeli," although her intentions - to document a lifestyle, to create timeless imagery out of daily life - are the intentions of artists who live in many places.

Her new work shows a romantic sensibility, filtered through post-modernist distancing effects, that is mature in its vision and realization.

In one body of work, Laor made still images of people in a public park in Jerusalem that she had clandestinely taped on digital video. The small figures, photographed from a great distance, possess the timeless quality of people from biblical stories. The golden light suggests Italian cinema from the postwar period, and the figures seem to be occupying stage sets. One image of four women in long dresses is reminiscent of paintings by French Barbizon painter Millet.

In her other series of digital photographs, Laor again takes pictures of unsuspecting people. This time her subjects are Orthodox Jewish women, who in their long dresses and scarves look as if they are from another age. In one print, a girl with friends looks back toward the photographer, catching her at her game. The girl looks unsettled, but she offers no menace.

Untitled #120, 2001-3, Lambda print

Leora Laor Israeli artist Leora Laor is working in territory that's being explored by lots of contemporary photographers: the relam of the cinematic, or the quasi-cinematic – i.e., images that look like stills from surveillance video or avant-garde cinema and that sweat ambiguity through their pores. But few do it as well as Laor whose digital prints portray figures is an ambiguous landscape (the "Image of light" series) or orthodox women and girls in Jerusalem (the "Wanderland" series) with the blurry, snapshot effect that secures a sense of mystery and odd authenticity). I was unfamiliar with Laor's work before seeing this modest exhibition, which suggests she's an artist to keep an eye on. Through March 30 at the Ellen Curlee Gallery.

De foto's van Leora Laor (Jeruzalem, 1952) tarten de grens tussen fotografie en schilderkunst, tussen het echte leven en het in scene gazette leven. Het wordt nooit duidlijk wat echt is en wat gemaakt.

Leora Laor begint haar carrier als freelance fotografe in de tijd dat zij film, televisie en geschiedenis studeert aan de Universiteit van Tel-Aviv (1973-1983). In 1979 verhuist zij naar New York, waar ze eerst fotographie studeertaan de School of Visual Arts en verovolgens lessen volgt bij de fotografe Lisette Model (1901-1983) aan de New School of Social research. Laor wordt huisffotograaf bij galerie Oggi Domani in de East Village, op dat moment de enige galerie daar die zich richt op fotografie. Zu heft er in 1983 haar eerste eenmanstentoonstelling. Laor fotografeert vooral het steeds weer wisselend straatbeeld. Halverwege de Jaren tachtig krijgt ze twee solotentoonstellingen in de Bess Cutler galerie in Soho. In 1984 doet zij mee aan de groepstentoonstelling 'Landscapes and Mindscapes', in Brussel.

Prizen

Eind jarn tachtig keert Laor terug naar Israel. Ze is inmiddels getrouwd met de Israelishe kunstenaar Michael Sgan-Cohen, die eind jarn zestig naar New York was getrokken. In 1999 sterft Sgan-Cohen en Laor rich teen stichting op om zijn werk te

Archiveren. In 2004 organiseert het Israel Museum een overzichtstentoonstelling van werk. Na zijn doo den na een periode van bijna twintig jaar waarin Laor niet heft geeexposeerd, pakt ze de fotografie weer op, Immiddels woont ze in Jerusalem en haar fotoseries zijn allen gemaakt in Israel. Sinds haar terugkeer tot de fotografie, heft ze een aantal prijzen gewonnen. Zu wordt zij in 2005 gekozen als laureaat van de Leon Constantiner prijs voor Israelische fotografie van het Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Haar werk is ook aangekocht door een aantal musea over de hele wereld, waaronder door het Fotomuseum in Den Haag.

Sinds 2002 werkt Laor aan een aantal fotoseries, "Images of light". "Wanderland", foto's genomen tijdens danslessen en theaterfoto's. Hoewel de grens tussen echt en niet echt bij het werk van Laor niet duidelijk is, ensceneert zij nooit. Zij maakt gebruikt van, zoals zij zegt, 'ready made location'. De ready made locations kunnen zowel een gewone middag in een park in Jeruzalem zijn – de 'Image of light' serie –een dag in Mea Sharim – 'Wanderland' een – of een daadwerkelijk toneelstuk. Laor zal nooit iets aan een scene toevoegen. Van een afstand observeert zij en neemt zij de foto's, of filmt zij wat er om haar heen gebeurt. Pas later manipuleert zij digital het lich ten de kleur.

Veel van haar foto's hebben geen titel. Een van de hier afgebeelde foto's laat twee meisjes zein. Je ziet ze op de rug.Beiden hebben ze rood haar in en vlecht. De ene heft een groene jurk aan, de ander een zwarte overgooier. Beide dragenzwerte kousen en schoenen. Wie zijn deze meisjes ? Zijn het zussen, vriendinnen? Waar gaan ze naar toe? Deze foto deel uit van de serie 'Wanderland', een serie van 41 foto's uit 2003. Met de titel 'Wanderland' refereert Laor aan de 'Wandering Jew', tegelijkertijd duidt het word 'land' op het permanete. Het zijn beelden die Laor heft gekozen uit een video-opname die zij maakte van Mea Sharim in Jeruzalem. Op zichzelf hadden de beelden net zo goed op hum plaats kunnen zijn in de negentiende ceuw, maar de gebruikte technick verraadt dat het om modern foto's gaat. Nadat Laor vanaf grote afstand heft gefilmd, vergroot ze vervolgens de pixels zo dat de foto bijna verdwijnt. Vervolgents versterki zij de dominante kleur. Dit verklaart de intens groene jurk. En wanneer de foto is genomen, blijf je als kijker vooral met vragen zitten.

Spanning

De tweede hier afgebeelde foto is zo mogelijk nog intrigerender. Deze foto, zonder titel, maar met de toevoeging '(Hommmage to Osher)', laat een man en een vrouw zien. De vrouw heft een ouderweste gebloemde jurk aan en de man is in pak. Hoewel ze alkaars hand vasthouden, wekken zij niet de indrunk elkaar goed te kennen. De achtergrond is vaag, het lijkt niet op een huiselijk tafereel, eerder op een danshal. En wat betekent de toevoeging bij deze foto? Is dit stel echt of laten ze een illusive zien? Soms verdwijnt een deel van de spanning in een foto wanneer het raadsl wordt ontrafeld. Laor vertelt dat het haar spijt mensen teleur te stellen wanneer ze vertelt dat deze foto, mede door de toe voeging zo intrigerend, geen foto blijkt te zijn van een stel dat zij op een onbewaaki moment, tijdens danslessen, heft vastgelegt, maar van twee acteurs die in het toneelstuk Osher spelen. Voor dit stuk won Michael Gurevitch de prijs van regiseur vanhet jaar, en Renana Raz werd gekozen als beste choreograaf. Osher gaat over een man wiens naam Osher is. Osher betekent geluk in het Hebreeuws Hij woont in een flatgebouw en zijn ouders wonen een verdieping onder hem. Door het toneelstuk heen zijn zij allen op zoek naar geluk. De foto is er een uit de serie theaterfoto's die de fotografe in 2004 maakte. Met de naam Osher kun je, Aldus Laor. Blijven associeren.

Laor geeft er de voorkeur aan om haar foto's geheimzinning te houden, zonder veel uitleg of interpretaties.'Met mijn foto's laat ik zien: dit is wat het leven wil zeggen.' Het leven waarop we dingen zien en hoe diezelfde dingen door verschillende mensen op verschillende manieren kunnen worden geinterpreteerd.

Laor foto's laten duidelijk zien dat het soms beter is om gewoon naar dingen te kijken dan om er eindeloos over tepraten. Dus vergeet wat je net hebt gelezen en kijk alleen naar een spannende foto.

Werk van Leora Laor en andere fotografen is vanaf 29 oktober tot 18 februari 2007 te zien in de tentoonstelling 'Wanderland' in Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld (Duitsland). In 2007 zal werk van haar te zien zijn tijdens 'Dateline Israel', een tentoonstelling van recente fotografie en video in het Jewish Museum in thr New York.

Untitled #106, 2001-3, Lambda print

Fantastic, abstract imagery often serves the conscious as a memory or an obscure and vague object of desire that our imagination strains to capture. The human will to comprehend the elusive image as a complete object result in a disability rooted in limited perception while stressing the constant striving toward the unfathomable. This attempt to elaborate on the bounded yet unbounded human condition has been a central concern for philosophers and theologians who sought to define the individual's place in relation to the universe, the forces of nature and God.

Israeli photographer Leora Laor binds these phenomena of perception with human ephemerality displaying digital stills situating human figures on the enigmatic seam line bordering life and death, reality and dream, routine and fantasy. Laor deals with the tension between the limited and the un-limited, the finite and the infinite, urging the spectator to strive to comprehend the ungivenness of nature as well as human nature.

Images of Light were photographed during twilight hours or at night. Thus, in these images light exists but has no direct affinity to luminescence. The result is that figures occupy an urban landscape from which they are alienated. Laor uses her digital video camera to take stills, but is also deeply influenced by the continuous cinematic creation, filming short video clips from which she isolates individual frames. Both these technological processes allow her to create new dismantled works. The figures stand out clearly in the twilight from background where patches of light are cut through by dark shadows combined with intense color, creating an expressive atmosphere, principally stemming from dramatic backgrounds that provide fantastic scenery. Laor chooses to show the urban public park as no-place and the figures as anonymous. In situations where Laor "cuts" images from reality (she never stages them), the "picture" is built up or alternatively fades away. She creates an intensified object, boundless and timeless. Uncanny colors formulate a new unfamiliar setting where human figures seem to grow from within. As a result, the backgrounds seem chaotic, emphasizing the frail human condition and arousing primal inherent concepts and feelings of anxiety and death.

While photographing, Laor has tried to free herself from conscious thought and work intuitively. In this way she attempts to reach the irrational which is portrayed in the powerful and boundless landscape. In Image of Light #3 two people walk through the wilderness. Laor portrays her constant vision of isolated images wandering continuously in the wilderness. A mental picture which might be rooted in the fact that she is a second generation Holocaust survivor – her uncle was shot while walking and her mother roamed the streets. The frailty and loneliness of their lives is a central source of inspiration in her work.

The single lone image is portrayed throughout her work. In Image of Light #12 , a sole black silhouette of a woman is placed against a red-hued backdrop of emptiness. Laor develops the ideas of awe-inspiring nature, death, the sublime, and life's inescapable emptiness. The border where matter ends is emphasized. Like Ingmar Bergman's Totentanz – The Dance of Death (in The Seventh Seal ), Laor sets her figure on the border line between heaven and earth, emphasizing humanity's fragility and delicate temporality. This intensification of expression characterizes the Northern Romantic tradition. Casper David Friedrich attempted to revitalize the divine experience in a personal, secular world. The spiritual was displaced from traditional religious images to nature. Goethe stressed that infinite substance exists in man and in nature. Laor is concerned with this same idea. Although the woman in the photograph is frail, she is situated in the central axis of the composition manifesting, as in Freidrich's painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), the classical idea of a human being as a microcosm striving for knowledge. Gerhard Richter in his painting of the sea ( Untitled , 1973) evolves this thought while completely removing the human figure, placing the viewer at the edge. In contrast, Laor's figure is prominent but the landscape is unfathomable, it is a great abiding object. The role of the image as silhouette is to make peace with the abstract landscape. It is the dissolution of the image but it subsists despite its dissolution. The recognizable figure humanizes the amorphic void – the landscape. The photograph is seen as hallucination, a daydream or a fantasy where the image signifies the real, the connection to our objective world and as long as it exists we will not fall into emptiness. Laor says: "the main concept is inaccessibility, the un-limited we cannot get rid of but we can also not find, and this is exactly why it cannot be avoided".

In Images of Light Laor makes an interesting move by replacing the untamed and grand nature found in Romanticism for a municipal urban park charged with expressionism. She chooses to blur the categories ascribed to the external sublime and internal desire and anxiety. In unifying man and nature, she reflects the human condition as transience.

Laor's painterly way of thinking and striving towards emptiness is further stressed in her words: "A perfect photograph will be white upon white, the perfect balance which can be obtained by nothingness. If you take a scale, it is perfectly balanced only when it carries nothing." However, Laor is trying to reach the perfect void by material means which she chooses to dismantle to a point where the fleshiness of the print is exposed. Thus the print becomes a Memento Mori in photographs showing decaying red fruit with a fish or single enlarged images with sfumato contours situated in banal interiors. "The monotonous infinite dismantling is acted upon in order to erase the living truth which is unique and in order to transfer it to the neutral totality of death."

Image of light #12, 2003-4, Lambda print

Leora Laor's photographs at the Stephen Daiter Gallery are among the few digitally manipulated pictures I have seen that add to conventional photography and transform reality in an exciting and powerful way.

The artist has shot scenes with a long lens in a public park in Jerusalem with a video camera. She then used a computer to extract still images and work on their textures and colors. This has caused a superficial resemblance to the work of fellow-Israeli photographer Michal Rovner, though Laor's art is less conceptual and more than able to stand on its own visually.

Her pictures extract from common postures, gestures and deployments in landscape an atmosphere of apocalypse. Look at the work long enough and the images collapse again into the everyday. But they never quite lose all of their visionary aura, and as a result we see how the extraordinary is consistently based in the ordinary.

Some of the images are merely theatrical, when we feel the artist straining toward the mythic. But more often Laor succeeds in taking the posture or gesture beyond its immediate circumstances--so that the specific seems to aspire naturally toward the universal.

The artist exhibited frequently in the 1980s. After an absence, she resumed photographing only in the last five years. This is her first solo show in Chicago , and it's a strong introduction to a gifted artist in her 50s.

It will be fascinating to see where the work goes from here.

Image of light #14, 2003-4, Lambda print

By talking only minor liberties with the Hebrew , it's possible to render the name of Israeli artist Leora Laor in English as "my light", to the light". This is not only very cool from the perspective of those of us whose names don't mean anything interesting, it's also appropriate. Because the Laor pictures now on view at Daiter Contemporary draw their uncanny power-as well as their powerful uncanniness-from an intense negotiation between the world's light and Leora's own.Obviously, all the photographs depend on such a negotiation to some degree, the camera itself being the traditional site where the bargain is made. But Laor is able to bring extraordinary influence to bear on the process in her recent series. "Image of light", thanks to digital technology. The 53-year-old artist extracted individual frames from video of everyday scenes in a sunny Jerusalem park, blew them up, and suffused them with the electronic equivalent of colored washes. These washes interact with natural light and the inherent graininess of video to transform the photo's subject matter, sometimes radically, and sometimes not. The pictures in "Image of light" seem to fall into three categories of transformation. In category one pictures, wash in used purely to heighten a nominally natural color scheme, providing greener greens for the grass, wheatear ochers for dry ground, and the occasional accent of a very red sweater. This approach yields the most conventionally attractive, even bucolic, scenes of people at play.

Then there are the pieces in which the entire image is tinted a very pale yellow or green. Figures are reduced to silhouettes: men in short sleeves, women wearing snoods and long skirts in the Orthodox manner, the loose toddler. Caught against a lurid expense of sky or sward, they convey the same odd gravity you see in the statue like pleasure seekers in Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. none of whom seems to be having fun despite the pastoral surroundings. The anemic tones of these pictures suggest the burden of leisure, the melancholy attempt to have a good time on your day off, with your family, on public grounds. In fact they suggest work, alluding to Jean-Francois Millet paintings such as Washerwomen, in which the subjects are twilit from behind as they prepare to pound clothes beside a river.

With the third category Laor's imagery moves precipitously from the ironic to the iconic, a leap achieved entirely through a change of palette. Here the digital washes are all statured color, dense reds, yellow and oranges. In Image of light #3, a man and woman walk along a black ridge under a black sky, the deep yellow glow that illuminates them suggesting a biblical scene by Rembrandt. They could be Sarai and Abram walking to Egypt. Adam and Eve leaving Eden. In Image of light #2, a couple appear to be gathering possessions while their son stands by; the vista behind them is love like with yellow and orange. Again I think of Genesis: Lot and his wife abandoning Sodom. Of course, I know these thoughts have a good deal to do with my awareness that Laor took the photos in Jerusalem. But they have more to do with something timeless and apocalyptic in the images themselves. It doesn't matter that the woman on the black ridge is wearing a light knee-length skirts and a cardigan sweater or that the man carries what may be a big plastic bag. Laor's light takes them out of chronology altogether, placing them in what Alan Ginsberg called the "total animal soup of time". They are here and not here, early late, and the physical setting only adds to the mystique-since, after all, where does time behave more like soup than in Jerusalem?

Image of light #2, 2003-4, Lambda print

Leora Laor creates an enigma and a tale, a contrast that arises from her photos and the way they are set up in the gallery.

Laor, a photographer who was active in Israel and the US in the 80's, has recently resumed her photography. These photos have been exhibited in one-man exhibitions in New York, Chicago and Paris, as have the "Wonderland" and" Images of Light" series, of which a single video frame, digitally processed, is exhibited in the Israel Museum in the "Oorim" exhibition. In Dvir gallery Laor shows her latest works.

The enigma relates mainly to time, the time in which the photos take place; a time which is not real but rather borrowed time, theatrical time or time of the theatre of life. The artificial digital processing of the light and images enhances the sense of fantasy. The fact that some of the photos are single frames taken from a video film gives them an element of inner movement. Also the "real" photos have a theatrical air, where time is borrowed, in the melancholic escape to the ball room dance halls (Images from Ettore Scola's film "Le Bal" come to mind).

Remarkable is the way Laor treats the photos of the theatre stage, as if they were pictures of real life. She erases the line between the two, and the actors and the set become unknown heroes. It is this duality that creates the enigma, and the technical aspect, the synthetic realism, completes the beauty of the picture.

The way the pictures are set up in the gallery reedits, like cinematic editing, the series Theatre, Dance Hall and Still Life in an emotional and sensual fashion. The editing also emphasizes the notion of a riddle, and the spectators move through pieces and bits of stories, trying to reassemble them. In the picture "No Title (A Tribute to Happiness)", the theatre scene resembles Gerhard Richter's works of photographic painting, in that the blurred contours express an outer and inner movement, a blur that vibrates form the black and whiteness of the suit of the man, who holds the hand of a woman wearing an old-fashioned floral dress. They are distant from one another, their faces are nearly erased, and the spotlight seems like a sunset. Theatre and real life fuse together into a poem of late love. Laor processes the tone and light of a photograph taken without the flash, of a dance hall that appears to be nearly static, until the desired texture is achieved. The bodies are illuminated in a Flemish-like light, and the black hair of the dancing woman dissolves into the surrounding darkness. The photo suggests the presence of other couples; a hint of a wall and a mirror enable the reconstruction of the entire hall.

A black and white photo describes a large and shiny clay cup sitting on a table cloth littered with crumbs. It is a rustic and coarse still live, as if taken from an illustration to an old Spanish book. Next to it is a color photo of a fair middle-aged man, who looks like he belongs to another decade, sitting in a foreign bar. The light is melting away his figure. He stares at us in a suspicious, slightly feminine look. In front of him are numerous beer glasses and behind him, framing him, hangs a large obscure painting on a theatrical scarlet piece of velvet, which stirs up thoughts of having the last drink.The combination of the clay cup and the bar scene creates something almost mystical.

Like a solitary stream of bright light is " Alma ", a photo that alludes to the serene portraits of girls by Reinke Dijkstra. With her penetrates daylight into the nocturnal and theatrical scenes, like a stream of the present, of exposed life among the fractures of veiled reality. It is a real photograph, not digitally processed like the others, an exception that does not reflect on the rest. Youthful and sensual Lolita, beautiful in her red top, stands alert yet somewhat shy; her gaze turned away.

Further along is a close-up of a light bulb hanging from the ceiling and casting its light on it. This photo exposes the light and darkness, the source of light that gnaws at the darkness, in a brilliant composition.

Another photograph of the dance hall. The figures move in a solemn and romantic elegance; the light that is projected from the bodies is soon swallowed up by the black clothes, and in the corners the shadows are dancing.

Laor photographs also still life that is stained and that yearns to other times. The picture seems to be taken from a distant past where the colors were enriched and artificial: a picture of glossy fruits and berries, and beside them a wooden or porcelain fish, which emphasizes them being preserved in poetic artificiality.

In another photo, a man's face emerges from the dark, and the warm light seemingly melts away the flesh of his face and beautiful lips, and the whiteness of his shirt turns into real florescent light. His profile, with the sideburn on his cheek and the felt hat on his head, reminds one of a Bavarian character taken from an early film by Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

The four pictures together, the light bulb, the dance hall, the still life and the man's face, compose a small play in four acts.

A woman who appears in the above mentioned picture is in another one holding a woman with short hair, and the blackness of their clothes merges them together into one entity. The light is Vermeer-like yet grained, thus creating mysterious yet extremely worldly and feminine characters. It is a brilliant composition of intimacy that exists in dance, which shivers around the edges.

The most enigmatic picture is "A Tribute to Adultery", a large black and white, theatrical and at the same time documentary photograph. It describes a dim stage, and on it is sitting a man in cotton pants and bare torso, in a position like a boxer. His face is distorted by the stage light that comes down like a beam and falls on the empty bed of fornication. Above, on a small screen, is the year 1968, apparently a time different from the real one. The table, bottle and glass on the right are blurred into a mirage. Although this is a picture of the theatre, there is a deceiving essence of reality in it.

"A Tribute to a 110 Heart Beats", a large and long black and white photograph, is rested against the wall and thus completes the standing position of the woman that is described in it. She is in the dark and wears a white turban that looks like a halo around her head. Her aging face is heavily made up, and in her light colored clothes she seems to be awaiting things yet to come, perhaps Fassbinder's character. The combination of the boxer and the dancing women creates again a story with no plotline.

The exhibition ends in "Portrait of a Woman", which describes a bigger than life-size figure, who contains in her both real life and the theatre. Her face expresses strength and despair. It is the profile of a young woman whose seriousness is like that of an old woman, whose utter sadness is projected through every molecule of her body. Her hair is thick and black and the collar of her black coat is wrapped around her head like a wing. She looks like a Madonna for those doomed to a life in exiled, amazingly stoic and tragic.

In the context of quality of material and light, longing for another time, and brief encounters with other worlds, one must mention the highly recommended film "2046" by Wong Kar-wai, which processes realistic/fictional material into cinematic poetry.

Portrait of a Woman, 2005, Digital C-print

Leora Laor's beautiful and polished solo exhibition at the Dvir Gallery avoids, for the most part, the common photographic cliches that make it hard to tell different artists apart. Having said that, one work - a portrait of a girl - is entirely out of place in a show in which even the weaker works are distinguished by their fragility and vulnerability. It recalls the work of Dutch artist Reinke Dijkstra or the German artist Thomas Ruff, or any one of the hundreds of photogtapher students who followed them .The works in the show were all done over the last two years, since Laor's return to full artistic activity after a break of almosttwo decades. The results make it clear why her comeback has been so successful. The exhibition contains three series of photographs, though not displayed as separate groups. One is the theatrical performances, another of dance lessons, and the third of still lifes. In all cases Laor has crafted staged moments of reality, which filter out some of the roughness, the arbitrariness and the danger of the real thing. To viewers who are anaware that the subjects are staged, the photographs of theaters and dance schools may seem "normal" reality. The work "Untitled (A Tribute to '100 Heartbeats a Minute')", in which the references to an Israeli play, is espacially fine. The long, narrow black-and-white photograph (170 x 85 cms), which stands on the floor, leaning slightly against a wall, contains the somewhat forlon figure of a woman. It is a digital photograph, edited by computer ; but Laor manipulated it during the printing - the tradional way of altering a photograph - achieving a soft but unblurred pictorial quality. "Still Life with fish" - a photograph of red and purple fruit and vegetables next to a fish - conveys an especially strong sense of artificiality. There is something disquietling in the composition, a sense of things going awry. Does that feeling derive from the fact that the fish is lying next to the fruit bowl, rather than within it? Or from unconventional nature of the still life composition? Or thesense that Laor addresses still lifes as a genre that needs to reinvent itself, to favor "still" over "life", making death (as represented by the fish) the focus? The answer is unclear. The strong emotional impact of the work is mitigated by a far more tradional, black-and-white photograph of a pot-bellied jug, radiating its own internal light, like a classic still life. Laor's compassionate look at dance lessons makes no effort to expose loneliness or ragged corners, but concentrates gently, on movement and intimacy. The viewer, as a result, is invited to discover a measure of optimism in the quiet and introspective works, as if they signal a possibility of communication. The knowledge that the photography was done in a dance school, to which people come to be refashioned, to spend a little time in a different world, to be immersed in a harmless escapism - only strengthen the not-unpleasent sense of melancholy that infuses it. The point of departure of the theatrical photographs is a stage play, but the pictures are not documentary in character. The nonarchial feel comes not only from the deliberate blurring of the figure, but also from the choice of small moments. In "Untitled (A Tribute to Happiness)", a couple are holding hands and talking, but seem clearly ill as ease. The long blue curtain in the foreground establishes the context as a stage set, not a home. In her exhibition, Laor comes across as a seeker of sheltered and well-ordered places like dance schools and theaters, blending them to her will to create a still life composition. At the same time, she keeps her distance from them, avoiding the sharp detail and identifying feathers of the documentary - or the mien of the interrogator.

Untitled (A Tribute to "100 Heartbeats a Minute"), 2005, Lambda print

Leora Laor's photographs underline the tension between private and public territory, formulating the modern urban self. Her vision is deeply influenced by cinematic conventions, yet the act of shooting situates the image in reality. The works presented here are taken from two series entitled Wanderland, 2003-4. The title Wanderland enfolds a double meaning in both name and image. Wander concerns human wandering in general and the Jewish wandering wand and history. It is opposed to Land which signifies permanence and deep-rootedness. Counter to this, stands the magic Wand held by the divine creation as well as by human creation, which are satisfied by the artist.

The first series, Images of Light, was taken in a public park in Jerusalem. The photographs carry a sense of awe to early modernism. The images shown here are characterized by a pictorial look connecting the digital image with the impressionistic and expressionistic compositions and brush work (from Courbet and Millet to Munch, Kirchner, Balla and others). Laor enlarges the pixels to a limit where the image is dismantled and the picture plane is redefined as a technological creation. It also becomes an application and expression of the picture as a code and map. Laor succeeds in connecting historical iconography and style with temporary works reminiscent of Gerhard Richter, setting the ambivalent nature of effacement realism.

In Image of Light #4, the running figure wearing a dress and carrying a basket signifies the naive and the legendary ideal order, as opposed to the depicted dynamic abstract background. This creates tension between the individual and the world emphasizing a horrendous contrast. A flight performed in a hostile landscape defines modernity's radicalization as a juggernaut realm. The elusiveness of the figure, situated in a large background, emphasizes its fragility and evasive nature. The photograph itself is a material remnant of a fleeting and evasive reality that is created in the combination with lightened substance. Susan Sontag views the unnoticed light, in relation to the photograph, as a "flashy medium", that is to say substance. Hence the theme of the work exists in the triple tension between light, matter and human landscape.

The second series, Untitled, is taken in Mea She'arim, an ultra-orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem. Here, Laor seeks to define the human urban condition at its extremist, choosing her sights where she can examine the self as seen by the 'other'. From this perspective her work not only documents or deals with aesthetics, but with ethics and social concerns. All the different aspects establish her definition of the self, its boundaries and its relation to the world.

Image of light #4, 2003-4, Lambda print

All contents © copyright Leora Laor. All rights reserved.